Client

As the nation’s largest nonprofit organization dedicated entirely to health and well-being, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) is working alongside others to build a national Culture of Health. Through collaboration, research, and investment, RWJF aims to bring about meaningful, long-lasting change that will transform not only our systems and practices, but the way we think about health.

Geography

US / Nationwide

Topic Areas

Community Development

Economic Inclusion

Health

Youth Development

Project Types

Programs & Services

Visual Identity

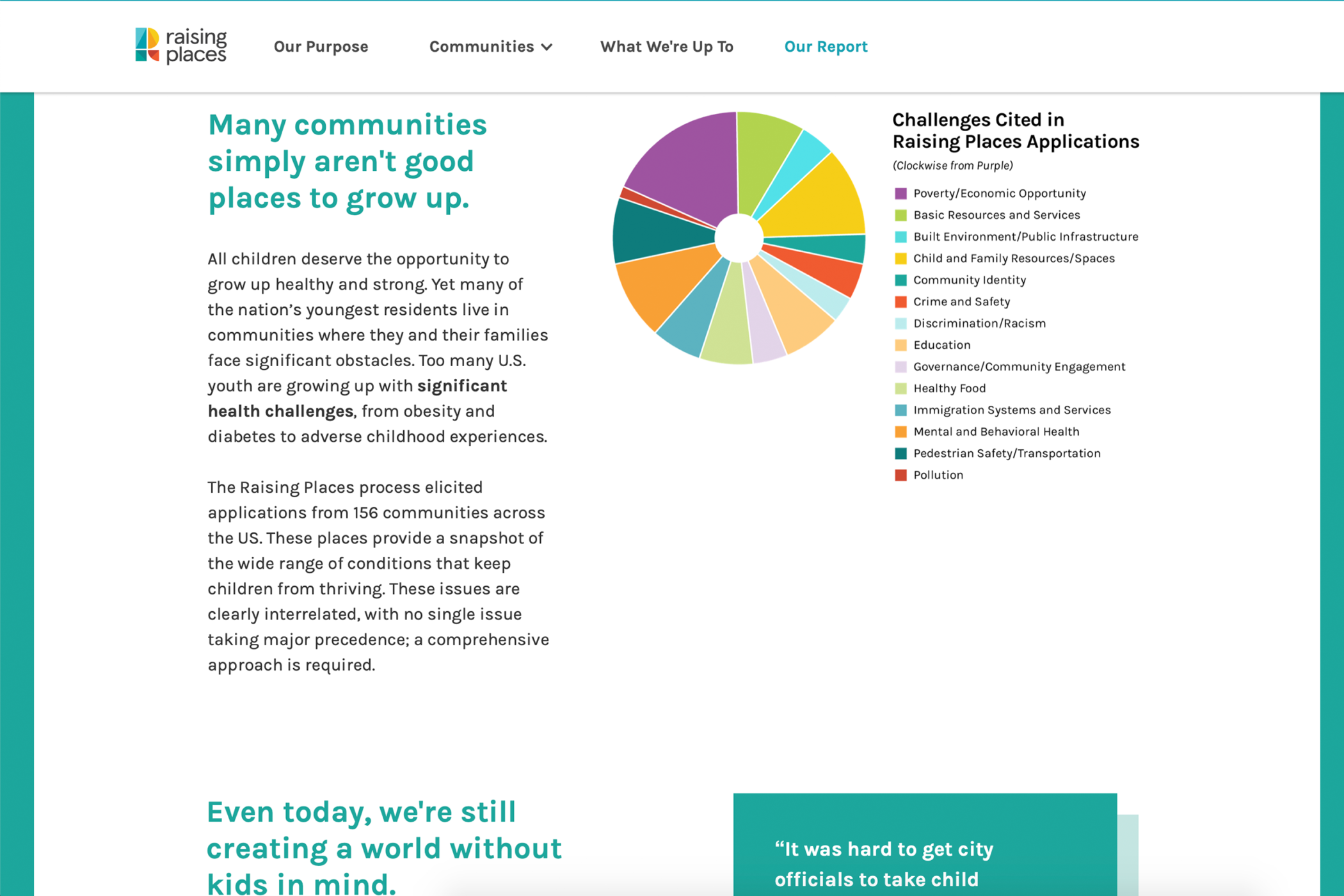

Our physical environment plays a powerful role in shaping who we are. As children, the air we breathe, the quality of our housing, the places in which we play and learn and experience life all contribute to our overall well-being—not just during childhood but well into adulthood. But while some children have access to environments designed to foster health and wellness, many others aren’t afforded the same opportunities.

Supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Greater Good Studio designed a program to move beyond the research on “kids and place” to take action and develop sustainable solutions.

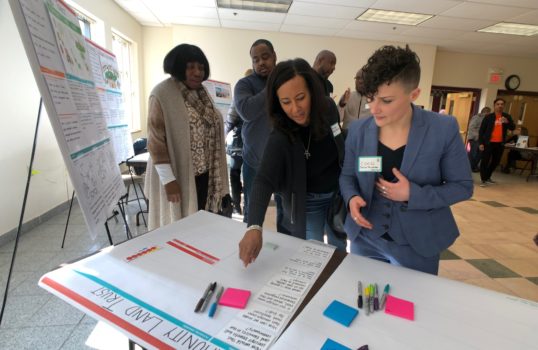

Using the model of innovation labs, we worked alongside urban, rural and tribal communities across the U.S., bringing together the people focused on “better childhoods” and the people focused on “better neighborhoods.” These local, cross-sector design teams created and launched a wide range of concepts that support their communities in becoming places where all children and families can thrive.

Project Outputs

Programs

Each community piloted a range of concepts for programs and projects that would make their community more child-centered. One year later, many of these projects were still going — on average, 5 projects per community!

The pilot programs include a Hunger Coalition and Mobile Food Service in North Wilkesboro, NC; a Police Committee Accountability Team and Youth-Friendly Transit Schedule in Hudson, NY; a Positive Messaging Campaign and Local Arts Co-Op in Lodge Grass, MT; and a North Side Shuttle and “Sunlighting” Our Schools initiative Minneapolis, MN, among others.

Strategies

We believe that local work can have national implications, but it is imperative to capture and share learnings from that work with different audiences. To connect the local Raising Places work to the national conversation, we planned and executed a comprehensive communications strategy that included releasing regular updates via the Raising Places website, newsletter and social channels, hosting the Raising Places National Convening, and placing articles in global publications like Fast Company, Curbed, CityLab and U.S. News and World Report, as well as local outlets in project communities such as HudsonValley360 and the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

I often talk about the ripple effects of our work. Today I feel as if we are riding a wave thanks to all of you.

Tools

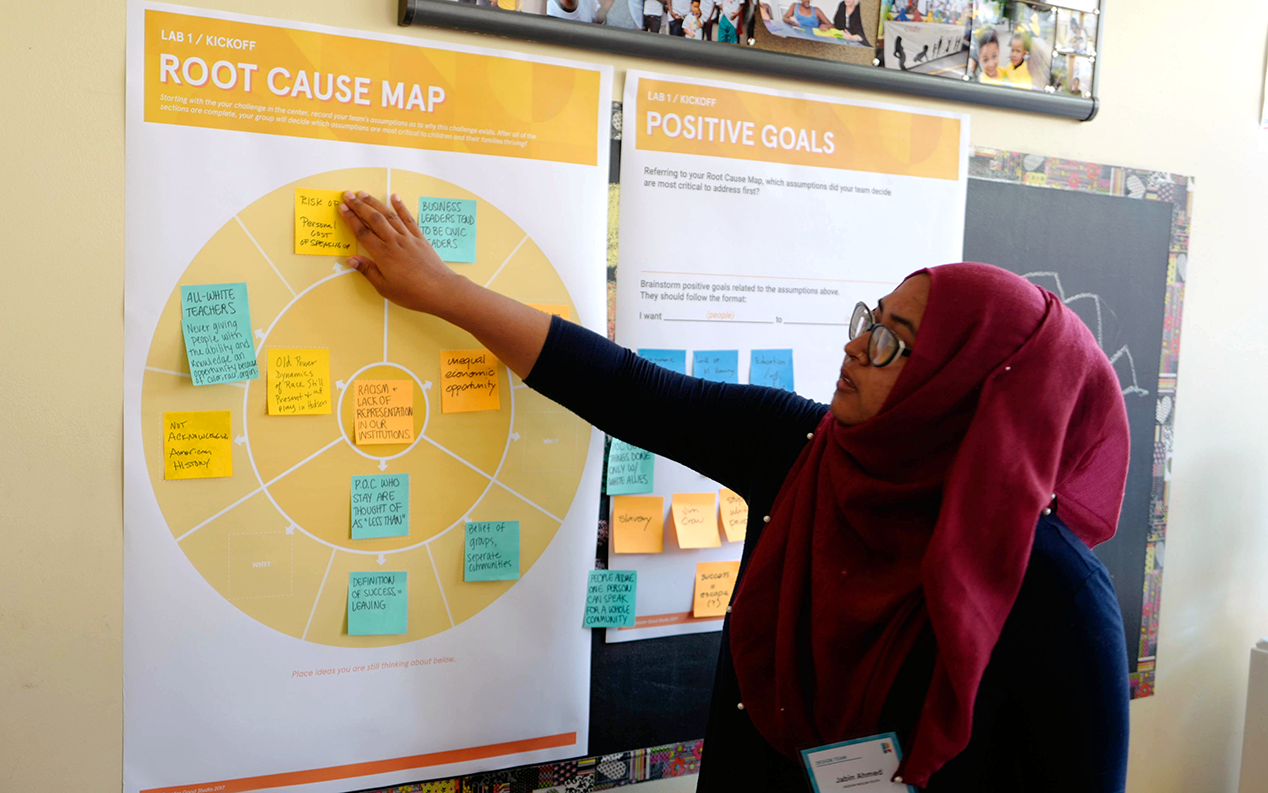

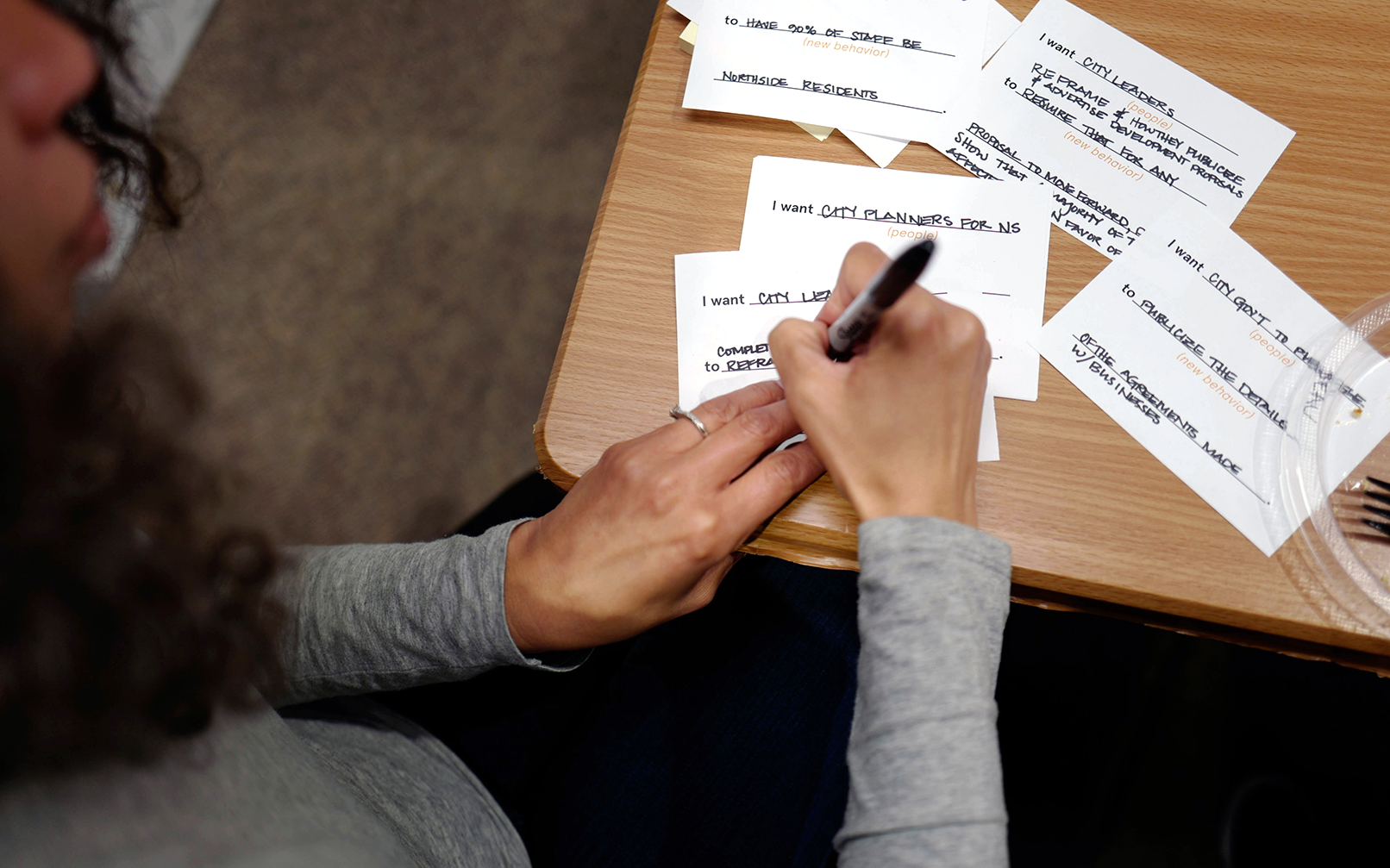

We created a new suite of tools for this project that have now been used across the six Raising Places community teams and beyond. Formalizing these tools — such as Root Cause mapping, which help teams uncover the reasons behind the challenges they experience, and Positive Goals, which frame the change we want to see — helped codify the community-based aspect of our curriculum.

Learning Experiences

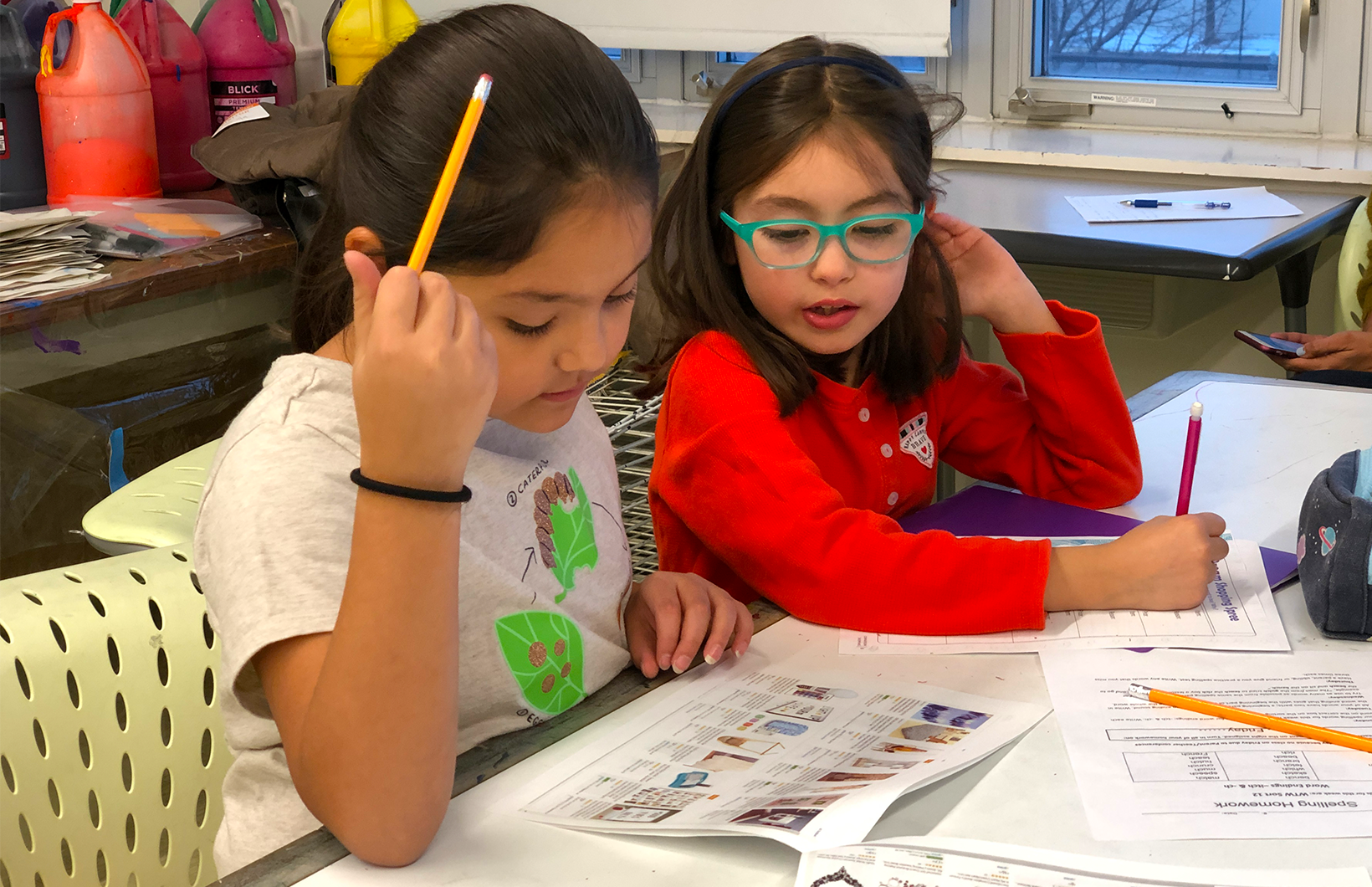

Every Raising Places convener learned how to more deeply incorporate cross-sector collaboration and community voice into their work, and every Raising Places design team member learned the human-centered design process by experiencing it firsthand. Design team members represented their projects publicly, such as at events and in meetings with people, to both raise awareness and garner feedback. This process allowed them to visualize themselves as local leaders and develop the capacity for creative facilitation and prototype testing.

The community stands to gain tremendously if these concepts are implemented, and I know the process helped open their eyes to what can be achieved with hard work and resources.

Client & Community Outcomes

Mindsets

This project underscored the power of human-centered design to change mindsets related to innovation and problem-solving. After the nine-month design process, 60% of design team members said they were more comfortable trying something new, 56% said they were more comfortable working with other people to create things, and 68% said they were more comfortable engaging end users (including youth) in decision-making.

The project also opened many stakeholders’ minds to the vital, yet often overlooked, strategic benefit of focusing on youth. “There is convening power in a child-centered framing. On the surface, it sounds really sweet, but it also allows us to step into the most challenging and complex issues that our communities face,” said Sara Kendall of Kite’s Nest, the Raising Places convener in Hudson, NY.

Behaviors

The Raising Places communities learned how to apply the human-centered design process to new contexts. Multiple design team members told us they incorporated the process into program and service areas that fell outside of this project’s scope. They identified practical tools or ways to promote collaboration and community involvement in moments like data collection and program design. Said one design team member, “We’ve always believed in cross-sector collaborations, but having a formalized structure to engage across sectors for these particular discussions was a valuable framework.”

Conditions

Through the Raising Places process, we created the conditions for creative solutions to flourish, multiple cross-sector stakeholders to be engaged and participate, people to rise to leadership positions and also elevate those around them, and local funders to believe in the innovative, community-altering work being done. All the pieces were already there; they simply needed space to come together.

Culture

Raising Places had a ripple effect on the communities engaged; the results have gone well beyond the original scope of the project. The process and the programs are only a piece of the outcome; the mentality that when a community comes together, considers its own strengths and needs, and collaborates to fill those needs—that’s where true culture change takes place.

To view the full project impact report, click here.

Team & Studio Impact

It’s hard to overstate the impacts this project had on us as a studio. Many of the tools and methods created for this project have formed the foundation of our community-centered design approach.

The assignment gave us the time and space to really consider our framework for engaging with place-based work. We learned that place-based projects are inherently more intersectional, more collaborative, and also in many cases more personal than organization-based work. People care a lot about where they are from, and many of our design team members both lived and worked in the communities we were focused on. Because of this, we needed to engage with people individually, while also bringing the group along. One-on-one conversations, small group coaching, and whole-group workshops were all critical formats for engagement.

This project also inspired us to codify new tools, such as Root Cause Maps, Positive Goals, and Pilot Plans. When you’re not the ones actually implementing human-centered design, you necessarily have to make your implicit steps explicit. Creating posters and templates and slides for these types of tools was extremely helpful – hopefully for participants – but also for us! We have used many of them in subsequent capacity-building engagements. We even designed and built a digital platform, Data Journal, to facilitate design team members sharing their observations and insights, and were able to use it on other projects with remote teams.

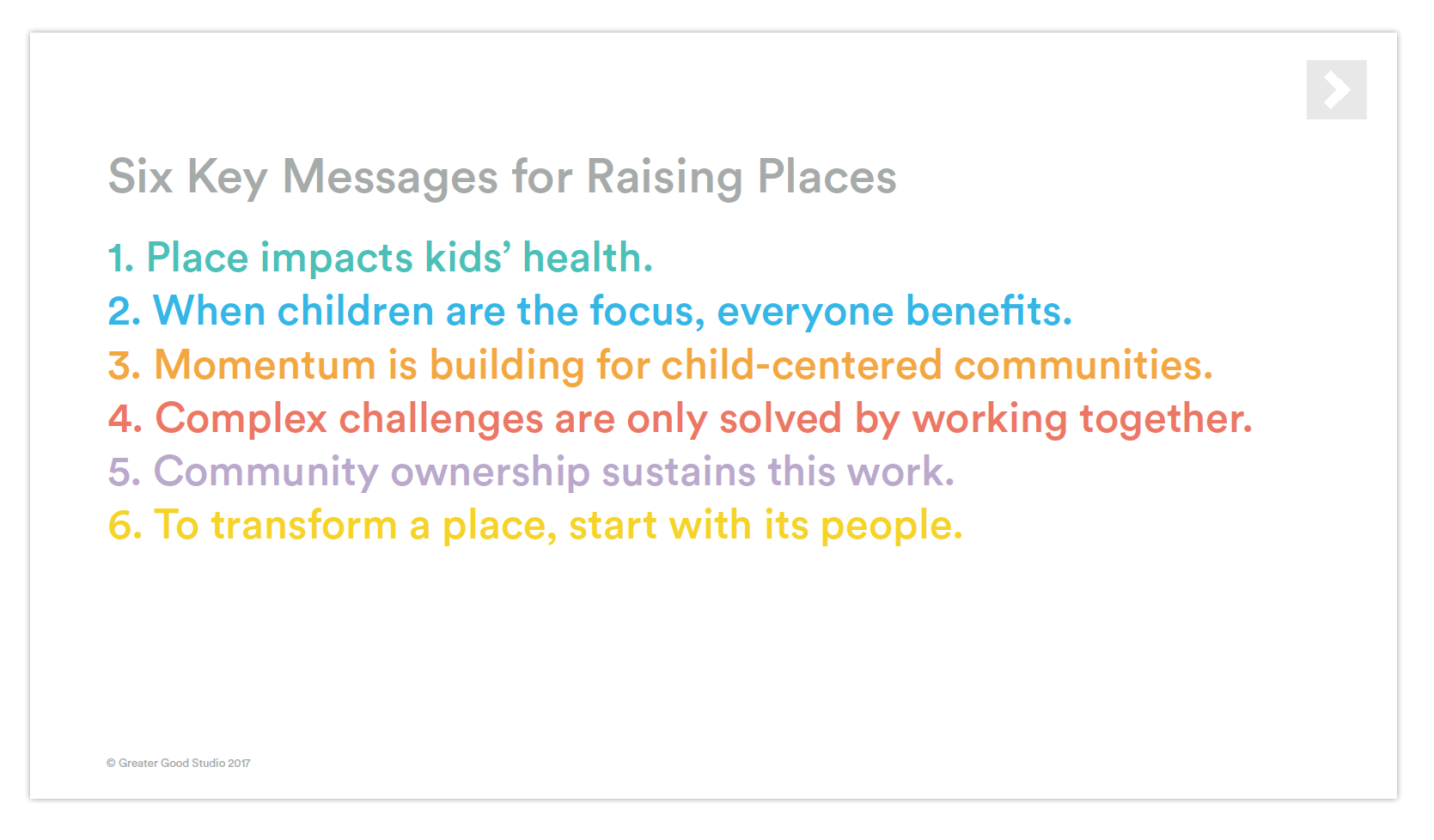

Finally, this project involved communications to a degree that we had never engaged in before. One aspect of the client’s theory of change was that we would undertake local work in a wide-enough variety of places that every community across the country could “see themselves” in the work. This meant building the capacity to talk about this work across many channels. We created a comprehensive messaging strategy and went through Strategic Communications training. We brought on a contract writer and photographer to document the Labs. We wrote and distributed a blog, newsletter, and social media campaign. We worked with a PR consultant to place the story in local and national media outlets. And, for the most part, it worked! Through all of this, we gained a much clearer understanding of communications as a lever for social change, normalizing and building demand for this type of child-centered community development with a range of audiences.